Court throws the book at “Yellow Page” business directory scam

Four closely related companies operating a business directory scam were ordered to pay an administrative monetary penalty (“AMP”) of $8 million as well as pay restitution to everyone who paid them any money. Two individuals behind the companies were ordered to pay AMPs of $500,000 each, and a third individual was ordered to pay $35,000. These are the largest AMPs ordered to date in contested proceedings.

The case establishes two important principles:

- Most communications between businesses and their customers, even invoices, will be considered “representations” that are subject to the Competition Act’s misleading advertising regime.

- Businesses cannot mislead consumers in large print and rely on the fine print to “clarify” the representations.

Anatomy of a scam

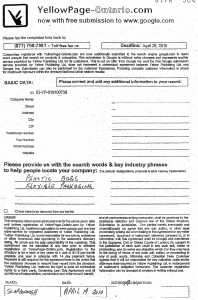

The companies all had similar names that began with “Yellow”: Yellow Page Marketing BV, Yellow Publishing Ltd., Yellow Data Services Ltd., and Yellow Business Marketing Ltd. They sent unsolicited faxes to thousands of businesses across Canada and several other countries that gave the misleading impression that the business was being asked to update information in a Yellow Pages listing. For instance, the faxes asked recipients to “correct and add any additional information to your record”; they included fake ID numbers, and real details about the recipients. The “dominant message” of the faxes was that the additional information was required because the service now included submission to Google.com. The faxes included a logo that mimicked the real Yellow Pages’ “Walking Fingers” design and the words “Yellow Page” (no “s”!) in a large type, followed by, in different lettering, the province, and “.com”.

Justice Lederman of the Ontario Superior Court held that the respondents intended to deceive many Canadian businesses into believing that they were dealing with the Yellow Pages Group (the real Yellow Pages) when in fact they were not.

Fine print is no defence

The fine print on the faxes stated that returning the faxes would bind the recipient to a two year contract costing $2,856.

The inclusion of this information in the fine print did not reduce the false or misleading nature of the faxes, Lederman J. held. The disclosure was not sufficiently prominent, nor did it clarify that the faxes had not been sent by the real Yellow Pages.

Indeed, many businesses appear to have been misled by the faxes: the Bureau received complaints from more than 1,400 Canadians.

Interestingly, fine print featured in another recent case: in June 2011, the Bureau reached a settlement with Bell Canada over claims that Bell was advertising prices that were not available, because Bell added various mandatory fees. The fact that the fees were set out in a fine print disclaimer was no excuse, according to the Bureau (see press release).

Promoting a business interest

One of the requirements of the Competition Act’s deceptive marketing practices provisions (and also of its criminal misleading advertising provisions) is that the representation must have been made to promote a product or a business interest, either directly or indirectly.

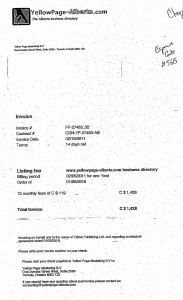

In this case, it was not only the fax solicitations that contained the misleading statements and branding; the domain names, invoice, reminder notices and letters also did. The respondents argued that documents sent to customers after the sale were not sent to promote a product or business interest, since the sale was complete.

Lederman J. disagreed, holding that

The phrase “business interest” must be given a wide meaning and collecting money, and threats made in relation to collection efforts, constitute promotion of the respondents’ business interests.

No due diligence

The respondents argued that the due diligence defence applied to them, since (they argued) the “Yellow Pages” and “Walking Fingers” trademarks are not distinctive and can be used by any internet directory publisher.

Lederman J. rejected this contention:

However, the exercise of “due diligence” in s. 74.1(3) is “to prevent the reviewable conduct from occurring” not that the Respondents had a genuine belief that the marks were generic. The due diligence must go to prevention and that is not the case here.

Aggravating factors increase AMPs

Lederman J. canvassed a number of aggravating factors that led him to impose AMPs close to the maximum. These included the fact that the respondents sent faxes to businesses all over Canada, including charities and small and family-run businesses. Thus, he held, the “recipients included vulnerable individuals likely to be adversely affected”.

Lederman J. held that it was unlikely that the respondents would correct their behaviour on their own. They did not correct their behaviour after findings made against them in other countries and a warning from the Bureau. They even breached an interim order form the Ontario court that they stop sending fax solicitations of the type at issue in the case until the hearing of the application.

Restitution and a bank account

Lederman J.’s order contains two novel features. First, he declared all contracts entered into between the respondents and Canadians to be null and void, and ordered the respondents to refund all money paid to them by Canadians. This is consistent with the Bureau’s submission that the entire business was a scam. The restitution order appears to be against all respondents, including the three individuals.

Second, Lederman J. ordered that the money in a bank account that had been frozen be transferred to the Commissioner. Presumably there is some money available to pay back consumers. Unfortunately, however, Lederman J. did not indicate in what priority the funds were to be applied. That is, he did not say whose claim would be paid first: the Crown’s claim for the AMP, or restitution to the victims.

International cooperation

The reach of the Yellow Page directory scam was truly international. The Yellow Page companies sent nearly identical faxes to businesses in a number of countries.

This resulted in a global enforcement effort. The Bureau worked with its counterparts in the US, the UK, and Australia.

In April, 2012, the Federal Court of Australia ordered Yellow Page Marketing BV and Yellow Publishing Ltd. to pay an AMP of A$2.7 million and to refund any amounts paid to them. The court prohibited them from continuing to send the misleading faxes and even from registering “yellowpage-” domain names (see ACCC press release and FCA decision). Lederman J. noted however that they had not complied with the order nor paid the fine.

Interim injunctions have been obtained against the respondents in the US (see FTC press release), and in the Netherlands.

Action was also taken against the Yellow Page companies by the owners of the real Yellow Pages trademarks before the Word Intellectual Property Organization. On March 15, 2011, a WIPO panel ordered that a number of Australian variants of the “www.yellowpage-” domain names be transferred to Sensis Pty Ltd. (the Australian licensee of the Yellow Pages trademarks) (see WIPO decision). A similar proceeding brought by the Canadian owner of Yellow Pages trademarks, Yellow Pages Group Co., was “terminated” because the Yellow Page companies have brought proceedings in the Federal Court of Canada to expunge the Yellow Pages trademarks. Yellow Pages Group can file a new complaint once those proceedings are over (see WIPO decision).

Lessens for advertisers

Yellow Page Invoice

Yellow Page is an extreme case, yet it holds a few lessons for all advertisers.

First, it clarifies that most, if not all, communications between a business and its customers will be considered to be “representations” made to promote a product or a business interest, and thus subject to the deceptive marketing practices/misleading advertising provisions.

Second, it is clear that businesses that issue ads or other communications that contain misleading statements cannot rely on the fine print to escape sanction. While any ad must be looked at as a whole, the fine print will get little attention from the court, just as it does from consumers.

The decision is: Commissioner of Competition v. Yellow Page Marketing, 2012 ONSC 927.